How did Julian develop this intense avoidance of medical procedures?

Was it unavoidable just because he has autism?

Is it something that his family and medical providers will have to deal with for the rest of his life?

No.

How Does Medical Procedure Avoidance Begin?

There are many aspects of medical appointments that can be challenging for someone with autism simply based on the characteristics of their diagnosis:

- Unfamiliar | A doctor’s appointment or visit to the hospital is not part of anyone’s daily routine. For someone with autism who has a preference for sameness and relies on a predictable daily routine for behavioral stability, just going to the appointment can create anxiety and increase the likelihood of challenging behaviors.

- Unexpected | Doctors' offices and hospitals are full of novel people, things, and unexpected events. Again, someone with a preference for sameness and routine may find navigating all of these challenging.

- Disorienting | Most medical settings are not constructed with sensory differences in mind. The sights and sounds may be distracting or upsetting for patients with autism. Some autistic individuals describe some types of sensory input as “painful” so it’s understandable how someone may want to escape or avoid that.

- Confusing | Typically, doctors and nurses use spoken language to explain procedures and let us know what is expected of us throughout the appointment. If a patient with autism struggles with using or understanding speech, these medical procedures quickly become unmanageable. In addition, what may look like a lack of “compliance” may just be a lack of understanding.

- Overwhelming | Autistic patients who use and understand speech fluently may still find communicating during medical appointments difficult. The pace of communication, the ability to focus when feeling overwhelmed by other aspects of the appointment, or the types of verbal and nonverbal language being used can all be problematic for someone with communication differences.

These are just some examples of how healthcare interactions can be difficult for autistic patients. Every individual with autism needs healthcare, and each has their own characteristics, differences and needs that can result in a lack of tolerance of needed medical procedures.

Avoidant challenging behavior can be as simple as refusing to go into the exam room or yelling no and pulling away from the provider. It can also be something more unsafe like hitting and biting others. When a patient displays any of these, parents and healthcare providers often understandably do whatever they can to stop that behavior in the moment. This most likely looks like ending or shortening the medical procedure and may also include added attention and soothing from a parent or some type of preferred activity like an iPad. While this stops the behavior during that appointment and keeps everyone safe, it may teach the patient that those types of behaviors work to escape or avoid something they don’t want. So, at the next appointment, in addition to still experiencing all the challenges already discussed, the patient might be more likely to exhibit those avoidant challenging behaviors again because they “worked” last time. As this goes on, these challenging behaviors may worsen and as the patient gets larger, healthcare providers may begin to refuse to provide care because it just isn’t safe. The patient may begin to even refuse to attend the appointment altogether, and their parents may begin to not even attempt to try because of safety concerns.

How Can we Prevent Medical Procedure Avoidance?

One of the best ways to prevent these unsafe avoidant behaviors is to proactively address the things about medical appointments that are difficult for someone with autism. Healthcare settings that prioritize and implement autism-friendly practices create environments that are more supportive and responsive to the different needs of their patients.

Some examples of autism-friendly practices in healthcare are:

- Flexible scheduling | Allowing the patient to come at a time of day that is the least disruptive to their schedule or providing a longer appointment time.

- Flexibility in healthcare practice | Being willing to make accommodations to how care is delivered whenever possible. For example, allowing a patient to ask for a break during a procedure or doing a procedure in a chair rather than on the exam table. Basically, if a patient with autism or their caregiver asks for some type of change to how care is delivered, providing it to whatever extent possible.

- Providing education to staff | Training all healthcare providers and other support staff on the characteristics of autism, different ways to communicate with patients, and how to calmly de-escalate agitation.

- Sensory accommodations | Making modifications to the setting to minimize visual clutter, dimming lighting when possible, providing quiet spaces, and allowing the patient to engage in self-stimulatory behavior when possible are all examples of ways healthcare settings can address the sensory differences of autistic patients.

Additionally, parents and healthcare providers can help prevent these types of unsafe avoidant behaviors from developing by:

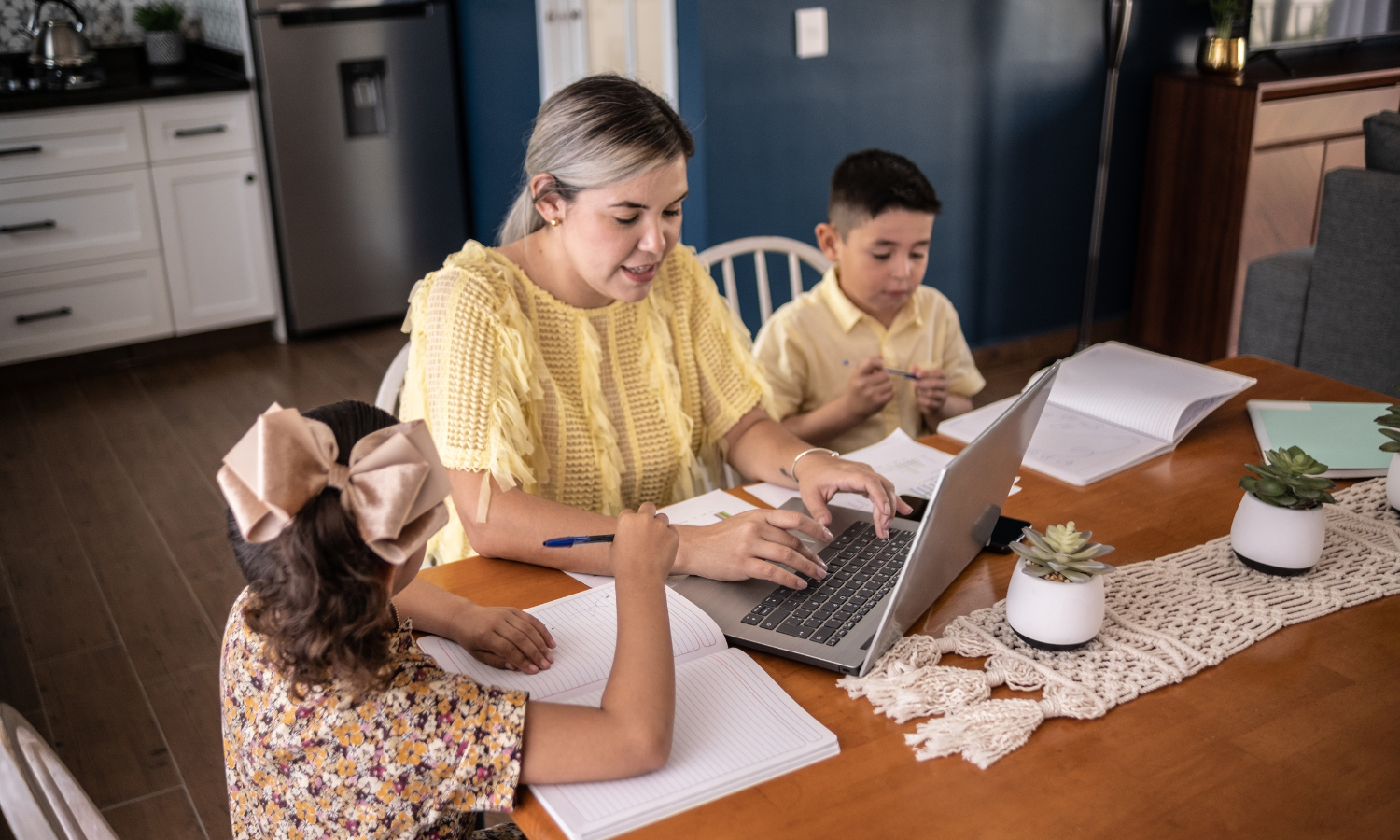

- Practicing needed skills proactively with strategies like social stories, pictures, and videos of procedures may be helpful for some individuals with autism to understand what is expected of them

- Using visual supports before and during appointments

- Using effective distraction strategies

- Reinforcing positive behaviors during medical appointments such as following instructions, allowing the provider to touch them with equipment, etc.

How Can We Treat Medical Procedure Avoidance?

Some individuals may still develop challenging avoidant behaviors. Thankfully, there are behavioral interventions backed by research that can compassionately and effectively address this. No patient should be forced to comply with a medical procedure, unless deemed absolutely necessary for their physical safety. Any intervention addressing medical toleration should analyze why these behaviors initially developed, assess the aspects of the medical environment that are aversive to the patient, and be responsive to the potential anxiety and trauma that the patient may be experiencing. In collaboration with a multidisciplinary team, an experienced behavior analyst can:

- Conduct a functional behavioral assessment of the challenging behavior

- Take baseline data to determine which, if any, aspects of medical interactions the patient will accept

- Begin an intervention designed to systematically expose someone to increasing amounts or steps of a medical interaction in a slow manner that also addresses the patient’s discomfort or fear

- Make data-informed decisions about when and how to progress through the steps of the medical procedure

- Provide effective reinforcement for appropriate behaviors that work toward the end goal of tolerating the needed medical procedure

These interventions can be quite time and resource intensive. However, when correctly implemented, they can greatly reduce the unsafe behavior a patient exhibits during medical interactions, increase the patient’s ability to access needed healthcare, and decrease reliance on sedation or restraints for required procedures.

Are you an autistic individual or caregiver for someone with autism? We want to hear about your healthcare experiences!

Are you a healthcare provider who wants to provide more autism-friendly care? Contact our Director of Clinical Initiatives, Lauren Frederick, M.A., BCBA at lfrederick@autismnj.org, to learn more about our Advancing Healthcare Initiative.

Are you an autism service provider who would like to help your clients or students learn to tolerate needed medical procedures? See our Medical Lending Library for support.

Allen, K. D., Loiben, T. Allen, S. J., & Stanley, R. T. (1992). Dentist-implemented contingent escape for management of disruptive child behavior. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 25, 629-636.

Chebuhar, A., McCarthy, A. M., Bosch, J., & Baker, S. (2013). Using picture schedules in medical settings for patients with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 28, 125-134.

Cho, M., & Choi, M. (2021). Effect of distraction intervention for needle-related pain and distress in children: A systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(17), 9159.

Cuvo, A. J., Reagan, A. L., Ackerlund, J., Huckfeldt, R., & Kelly, C. (2010). Training children with autism spectrum disorders to be compliant with a physical exam. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 4(2), 168–185.

Davis, T. E., & Ollendick, T. H. (2005). Empirically supported treatments for specific phobia in children: Do efficacious treatments address the components of a phobic response? Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 12(2), 144–160.

Davit, C. J., Hundley, R. J., Bacic, J. D., & Hanson, E.M. (2011). A pilot study to improve venipuncture compliance in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Developmental Behavioral Pediatrics, 32(7), 521-525.

Gillis, J. M., Natof, T. H., Lockshin, S. B., & Romanczyk, R. G. (2009). Fear of routine physical exams in children with autism spectrum disorders: Prevalence and intervention effectiveness. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 24(3), 156-168.

Hagopian, L. P., Crockett, J. L., & Keeney, K. M. (2001). Multicomponent treatment for blood-injury injection phobia in a young man with mental retardation. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 21, 141-149.

Jennett, H. K., & Hagopian, L. P. (2008). Identifying empirically supported treatments for phobic avoidance in individuals with intellectual disabilities. Behavior Therapy, 39, 151–161.

Meindl, J. N., Saba, S., Gray, M., Stuebing, L., & Jarvis, A. (2019). Reducing blood draw phobia in an adult with autism spectrum disorder using low-cost virtual reality exposure therapy. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 32, 1446-1452.

Riviere, V., Becquet, M., Peltret, E., Facon, B., & Darcheville, J-C. (2011). Increasing compliance with medical examination requests directed to children with autism: Effects of a high-probability request procedure. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 44, 193-197.

Shabani, D. B., & Fisher, W. W. (2006) Stimulus fading and differential reinforcement for the treatment of needle phobia in a youth with autism. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 39, 449–452.

Steusser, H. A., & Roscoe, E. M. (2020). An evaluation of differential reinforcement with stimulus fading as an intervention for medical compliance. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 53(3), 1606-1621.

Wolff, J. J., & Symons, F. J. (2012). An evaluation of multi-component exposure treatment of needle phobia in an adult with autism and intellectual disability. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 26, 344-348.