In the late 1990s and early 2000s, New Jersey’s autism community grew increasingly organized, vocal, and influential.

As the world approached the new millennium, autism advocates across the nation hit their stride. They were organized. They knew their rights. And they had finally had evidence-based treatments and legislators in their corner.

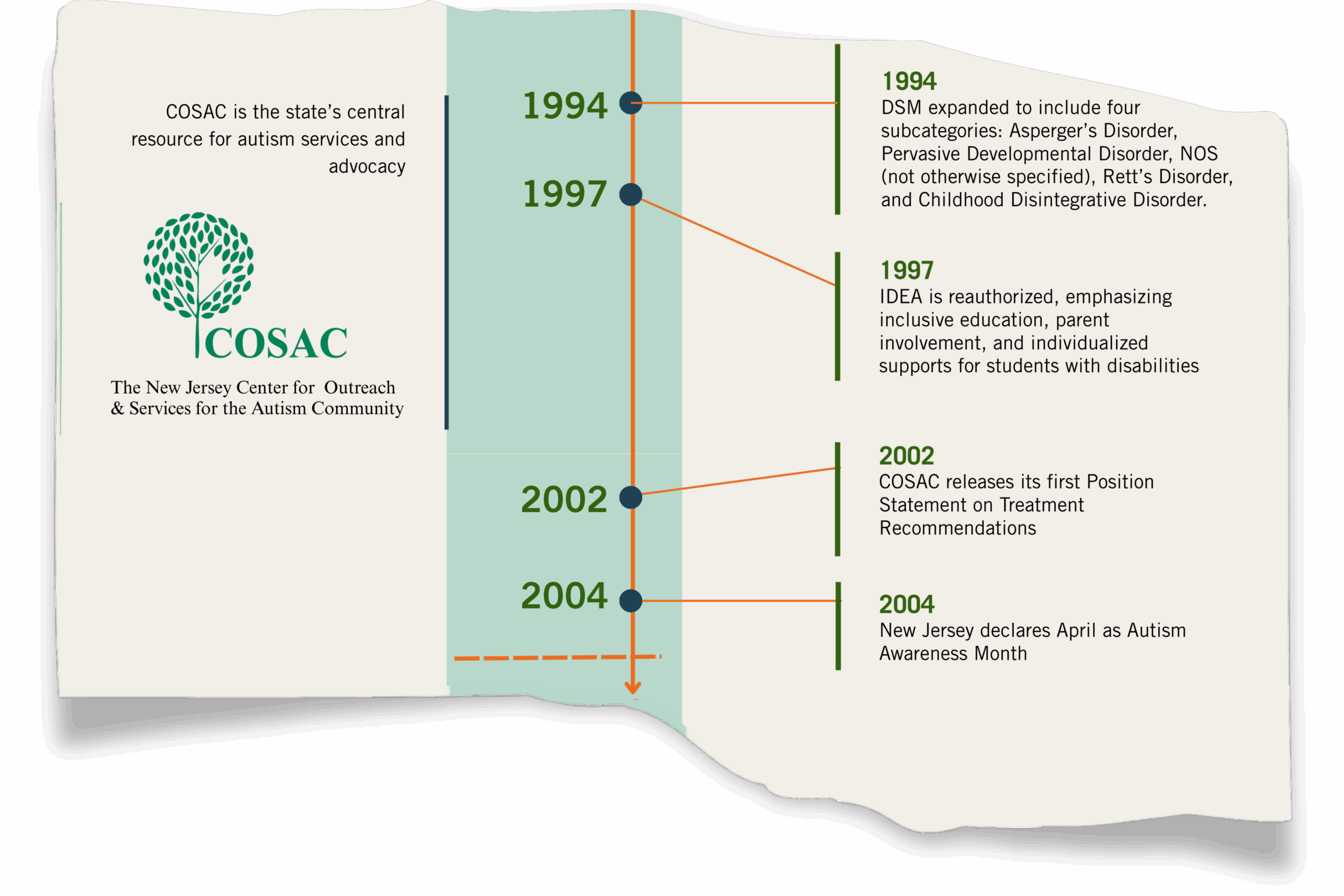

Following the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorder’s (DSM) expansion of autism criteria in 1994, more families flooded the system and advocated for services. Between 1995 and 2005 alone, autism rates grew from roughly one in every 500 children to about one in 110 nationwide.

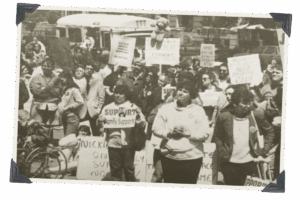

Families faced an uphill battle in many ways. An autism diagnosis often meant mounds of paperwork to obtain even basic services, inaccessible and inadequate educational programs and treatments; and individuals with autism often faced bullying and social isolation — but in many ways, the burgeoning autism community had found its voice, and parents and self-advocates demanded community integration, often achieving it.

In New Jersey, parent groups were a show of force. Meeting in church basements and local libraries, the groups taught newcomers how to request and vet an Individualized Education Plan (IEP); they invited special education lawyers to train parents to advocate for their children; and parents swapped notes on how to persuade the Division of Developmental Disabilities (DDD) into paying for much-needed services like in-home aides.

Announcements of these Autism New Jersey (then called COSAC) – sponsored support group meetings in South River, Scotch Plains, Hunterdon, Princeton and Ridgewood filled the pages of local newspapers.

Those same newspapers chronicled the battle between parents and communities over establishing group homes for adults with autism, as the de-institutionalization movement swept the nation and families looked to have their adult children integrated into society. In New Jersey, Governor Christine Whitman championed the move from developmental centers and institutions to adult day programs and group homes, ear marking money in the state budget to move individuals with autism and other developmental disabilities off the wait list and into new programs, according to Justice Helen Hoens.

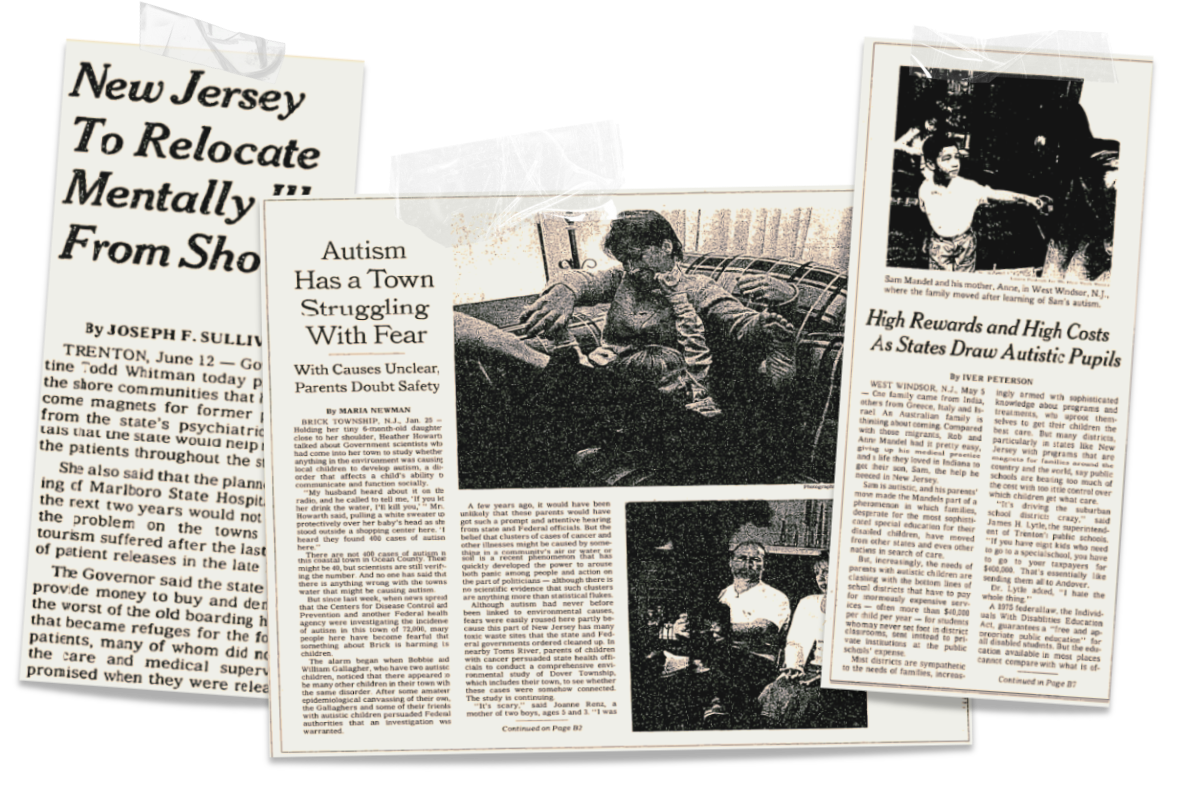

In 1998, two towns, Rockaway Township in Morris County and Englishtown in Monmouth County repeatedly made headlines for their residents vehemently opposing group homes in their communities. The Englishtown home, ironically on a street named “Hospitality Way,” sparked such a fierce controversy that Autism New Jersey Executive Director Nancy Richardson and her allies weighed in through pointed articles published in opinion pages.

While parents of older children with autism were focused on obtaining safe and appropriate housing, their counterparts with younger children and teens were making gains in the educational arena.

New Jersey resident Chris Gagliardi, who is autistic and was a teenager in the late 90s said his days were profoundly lonely when he attended his local neighborhood high school. But, because of a national legislative win in 1997 that expanded and solidified the IDEA to require schools to offer transition services for young adults, Gagliardi was able to enter Ridgefield Memorial High School’s Transition Program, and his future started looking up. Gagliardi — who said he started speaking his own thoughts, rather than “scripting” language and copying others at the age of 18 — rotated through different job training experiences to test out different workplaces, ultimately landing a position at Starbucks that he then held for almost two decades.

Yet, individuals with autism like Gagliardi still faced a kind of glass ceiling. For years, Gagliardi wanted to enroll in higher education, but it wasn’t until his 30s and 40s that post-secondary programs for adults with autism became available in his area. He recently graduated from Bergen Community College with his associate’s degree and is now attending Felician University where he studies journalism.

“Parents don’t know what they have today,” Chris’s mom, Lynda Grace Monahan, said. “Parents are so fortunate to have speech therapy, physical therapy.”

Hoens, whose autistic son, Charlie was in his tweens and early teens in the late 90s echoed the same sentiment.

“When you’re a parent, at first the news [of an autism diagnosis] is so devastating, you can’t even look up,” she said. “You’re just trying to move forward. It takes a while before coming to grips. For a parent with a severely affected child, it was a constant battle with someone about something.”

Hoens recalled asking DDD to provide an in-home aide of her choosing to assist Charlie, but DDD sent aides who were unqualified and unprepared to manage his severe challenging behavior. Several aides, once they realized caring for the 11-year-old would require physically intervening at times, quit on their first day. Eventually, DDD leadership authorized Hoens to hire staff from Charlie’s school, Eden, who understood Charlie and could help him apply what he learned at school at home.

Parents who raised their children in that decade said there was a substantial gap in services for their children. The therapies they needed didn’t exist and the ones that did were too broad to meet their child’s specific needs. However, compared to other states across the nation, New Jersey was well-resourced.

Specialized schools like The Eden School, Princeton Child Development Institute and Douglass Developmental Disability Center were a godsend for many children who could not receive a proper education in their district, Hoens explained.

“New Jersey was the place to be,” Hoens said. “For a tiny state to have three schools catering to students with autism. . . most states didn’t have any schools.”

Answering demand, more specialized schools and adult day programs opened throughout the state in the new millennium, often using the widely popular Applied Behavior Analysis (ABA) therapy to treat their students. A New York Times article from May 2000 chronicled the wave of families from other East Coast states to as far aways as India who uprooted their lives to move to New Jersey, to give their autistic children a shot at enrolling in one the specialized schools. To the frustration of some taxpayers and public school administrators, tuition for longtime New Jersey residents and new comers alike was mostly funded through local public school district budgets, with some minor help from federal funding.

Across the state, parents worked to get programs for students with autism up and running in their local public-school districts, too. In 1998, the Jersey City school district launched pilot “inclusion classrooms” where, with the help of classroom aides, students with autism learned side by side with their neurotypical peers. Meanwhile, a Burlington County mom quit her job to run an ABA-inspired preschool from her basement for her autistic twins, then successfully lobbied the Florence school district to create a program for local autistic students. The Star-Ledger’s Kelly Heyboer reported that these school districts benefited from this arrangement, too. They saved money on out-of-district placements and transportation costs.

New Jersey also led the way in autism research, following headlines of an alleged “autism cluster” in Brick Township in the late 1990s. Research later showed that there was only a slight statistical uptick of autism in the township’s population possibly due to the many families with autistic children moving to the area for its strong special education services. But the added attention to the “Brick Cluster” paved the way for landmark CDC studies in the state that are still producing reports and insights today.

In 1998, Andrew Wakefield published a (now debunked) study linking autism with vaccines, and with the wide adoption of the internet in the early 2000s, parents began to encounter other waves of misinformation about the disorder and its treatments. Scientists, doctors and science-informed advocates had to contend with “snake oil salesmen” who preyed on desperate parents — an ongoing problem even today, according to Hoens.

So, in 2002, Autism New Jersey released its position statement on treatment recommendations outlining its commitment to using science as a guide — a novel idea at the time — and endorsing ABA as the only available treatment with a substantial scientific basis for treating Autism Spectrum Disorder. This set Autism New Jersey apart from similar non-profits, who at the time, may have chosen to defer to parents with differing opinions, according to Hoens.

Two years later, the State of New Jersey declared April Autism Awareness month to acknowledge the four to seven out of every 1,000 children in the state who were diagnosed with autism at the time.

But it seemed for every advancement: every special education classroom opened, every community that welcomed a group home, and every study that was launched, the autism community still faced setbacks.

Sandra Fernandez, a mom with an autistic daughter from Toms River, wrote to the Asbury Park Press in the late 90s to describe a situation she witnessed while her and her daughter were out in their town: a group of girls made fun of her first-grade daughter for still wearing diapers.

For all the state’s progress in inclusion, her daughter was still getting bullied right in front of her, but Fernandez epitomized the unwavering, unapologetic spirit among autism advocates of that decade. She, alongside other parents and self-advocates, refused to back down and shrink back into the shadows of society, continuing to push more autism-friendly state in the new millennium.

Fernandez wrote: “I’m not going to hide my child because of a lack of understanding.”

Autism New Jersey: The Second Decade 1975-1985

Autism New Jersey: The Second Decade 1975-1985 From ‘Rain Man’ to Real Change: How Advocates Transformed NJ’s Autism Landscape

From ‘Rain Man’ to Real Change: How Advocates Transformed NJ’s Autism Landscape Breaking Barriers | How autism advocates rewrote New Jersey’s story for a new millennium.

Breaking Barriers | How autism advocates rewrote New Jersey’s story for a new millennium. As we documented Autism New Jersey’s history, we didn’t have to look too far into the past to find sources of hope. The organization, led by Executive Director Suzanne Buchanan, has been at the forefront of progress in autism treatment, safety and services over the past decade.

As we documented Autism New Jersey’s history, we didn’t have to look too far into the past to find sources of hope. The organization, led by Executive Director Suzanne Buchanan, has been at the forefront of progress in autism treatment, safety and services over the past decade.