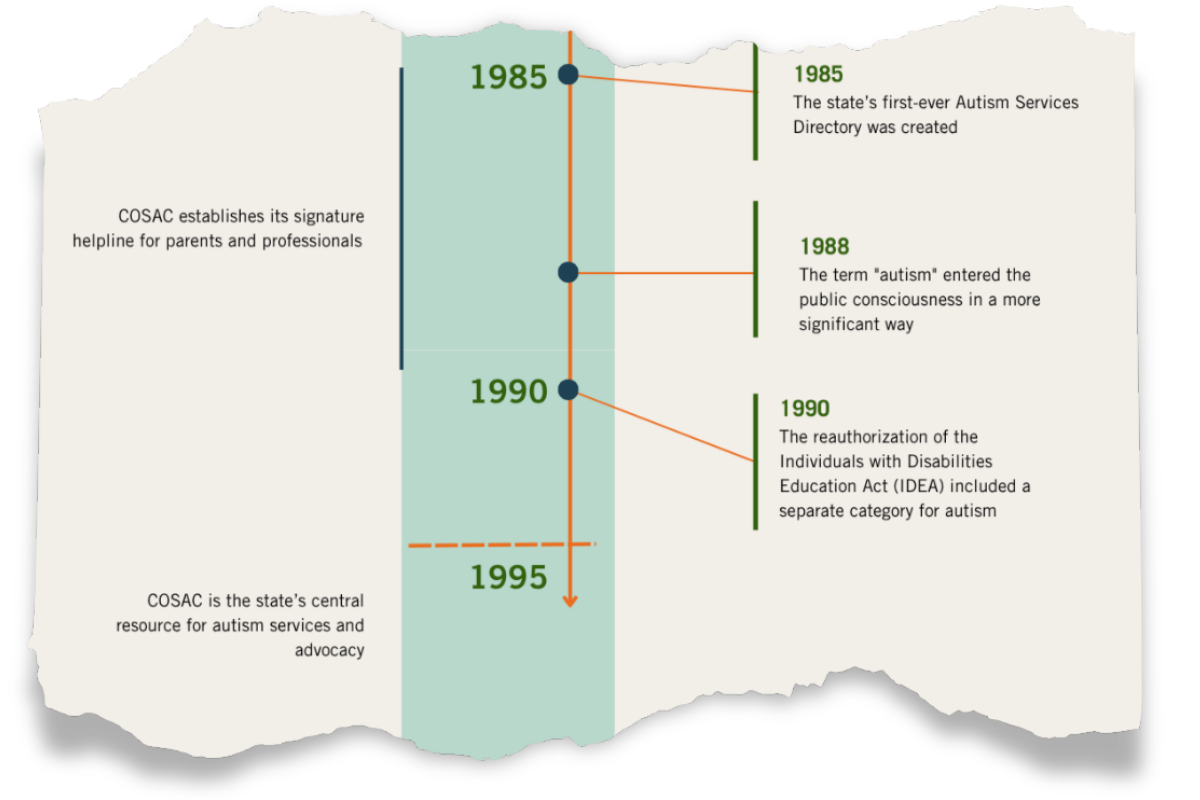

As Autism New-Jersey approaches its 60th anniversary, we look back on the history of our organization — and of the progress of the autism community, both statewide and national — through a series of six vignettes, published monthly. Read about our first and second decades.

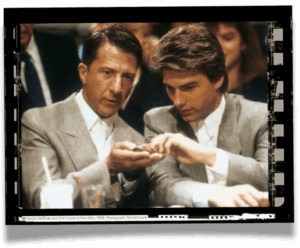

It’s 1988, and for the first time, autism was on the big screen.

For decades, parent groups like Autism New Jersey’s predecessor, COSAC, had been working to gain awareness for their children’s developmental disorders and funding for needed treatment and support. It was challenging work; at the time, only about one or two children out of 1,000 were diagnosed.

Of course, the movie was not without its issues. The main character was an autistic savant, with a special ability to perform complex calculations, leading to a widespread stereotype of individuals with autism that persists today.

Off-screen, advocates’ efforts gained momentum as they organized parent groups, shared educational resources, and pushed for a brighter future for their children.

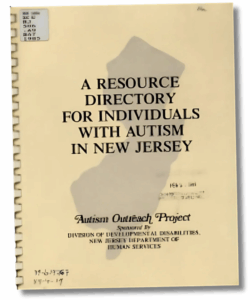

Brenda Considine, Autism New Jersey’s first outreach worker and second hire after Director Nancy Richardson, remembers that time well:

“We stood over a hot Xerox machine for hours, photocopying articles and information to send to parents,” she said. “[We] developed a library of print materials to help parents, including a brochure about our organization, a booklet on autism and a pamphlet on how to access extended school year services.”

In libraries and community centers throughout the state, Considine and Richardson organized parent groups, providing much-needed emotional support — Considine said the parents would group together in the parking lot after the formal group session ended, hungry to connect, and several groups eventually spun off to create their own local non-profit organizations. With an early commitment to evidence-based practices, the pair endorsed ABA therapy and brought in professionals to consult with the parents.

The pair also established Autism New Jersey’s signature helpline, fielding calls from parents and professionals alike and establishing the foundation for the organization’s current information services offerings.

“There were many late nights then,” Considine said. “There was a lot to do. There was no answering machine, no phone trees, no email … the phone rang and Nancy or I picked up. And if the person on the other end of the line was a parent, it was always Nancy who wanted to take the call — and she would stay on that call for as long as that parent needed to talk.”

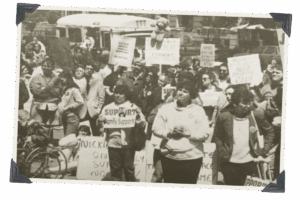

Considine and Richardson took note of the parents’ and providers’ concerns and brought them to the attention of law makers in Trenton. They partnered with the state’s major disability groups to increase government funding and expand educational service options and led the charge for passing the New Jersey Family Support Act, which gave families and individuals more choice in how they used government stipends.

As part of their campaign to pass the New Jersey Family Support Act, families visited legislative offices across the state to petition lawmakers. In an article for the New Jersey Council for Developmental Disabilities, Considine recalled a visit with a senator from the shore area:

“Initially, he was not all that supportive — he thought family support amounted to state funded baby-sitting. But with their children in tow, these parents forged on. Five minutes into the meeting, the flagpole in the office had been knocked over, there was a child under the desk, and another child who, at the age of 9 or 10, needed to have his diapers changed — and there was no place to do that in a legislative office. Needless to say, the Senator signed on to the bill. After being introduced to their reality, the Senator really got it!”

During that decade, Richardson and her team racked up other legislative wins that enhanced both housing and targeted educational opportunities for individuals with autism. On the national stage, advocates celebrated the reauthorization of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), which for the first time included a separate category for autism and mandated that schools develop a plan to help students transition to life after graduation.

Like many advocacy collations throughout American history, the autism community was comprised of various groups with differing needs, and they didn’t always agree. But when they worked together, they changed New Jersey and the nation for the better. The work of Richardson, Considine and other passionate families and advocates in the late 1980s and early 1990’s laid the groundwork for the start of a new Millennium, with more funding, more support, and more understanding for individuals and families navigating autism diagnosis.

Autism New Jersey has always operated on the power of connections, and we’d love to hear from you.

“Initially, he was not all that supportive — he thought family support amounted to state funded baby-sitting. But with their children in tow, these parents forged on. Five minutes into the meeting, the flagpole in the office had been knocked over, there was a child under the desk, and another child who, at the age of 9 or 10, needed to have his diapers changed — and there was no place to do that in a legislative office. Needless to say, the Senator signed on to the bill. After being introduced to their reality, the Senator really got it!”

“Initially, he was not all that supportive — he thought family support amounted to state funded baby-sitting. But with their children in tow, these parents forged on. Five minutes into the meeting, the flagpole in the office had been knocked over, there was a child under the desk, and another child who, at the age of 9 or 10, needed to have his diapers changed — and there was no place to do that in a legislative office. Needless to say, the Senator signed on to the bill. After being introduced to their reality, the Senator really got it!”

Autism New Jersey: The Second Decade 1975-1985

Autism New Jersey: The Second Decade 1975-1985 From ‘Rain Man’ to Real Change: How Advocates Transformed NJ’s Autism Landscape

From ‘Rain Man’ to Real Change: How Advocates Transformed NJ’s Autism Landscape Breaking Barriers | How autism advocates rewrote New Jersey’s story for a new millennium.

Breaking Barriers | How autism advocates rewrote New Jersey’s story for a new millennium. As we documented Autism New Jersey’s history, we didn’t have to look too far into the past to find sources of hope. The organization, led by Executive Director Suzanne Buchanan, has been at the forefront of progress in autism treatment, safety and services over the past decade.

As we documented Autism New Jersey’s history, we didn’t have to look too far into the past to find sources of hope. The organization, led by Executive Director Suzanne Buchanan, has been at the forefront of progress in autism treatment, safety and services over the past decade.