From Institutions to Inclusion: How New Jersey Parents and Advocates Reshaped the System

Richardson, a mom of two, knew something was amiss when her six-month-old son, Geoffrey, didn’t show emotions or respond to other people like his older sister had. But in the early 1970’s, information was scarce.

“We probably had not even heard of ‘autism’ when we started to say, ‘somethings wrong here’,” Richardson said.

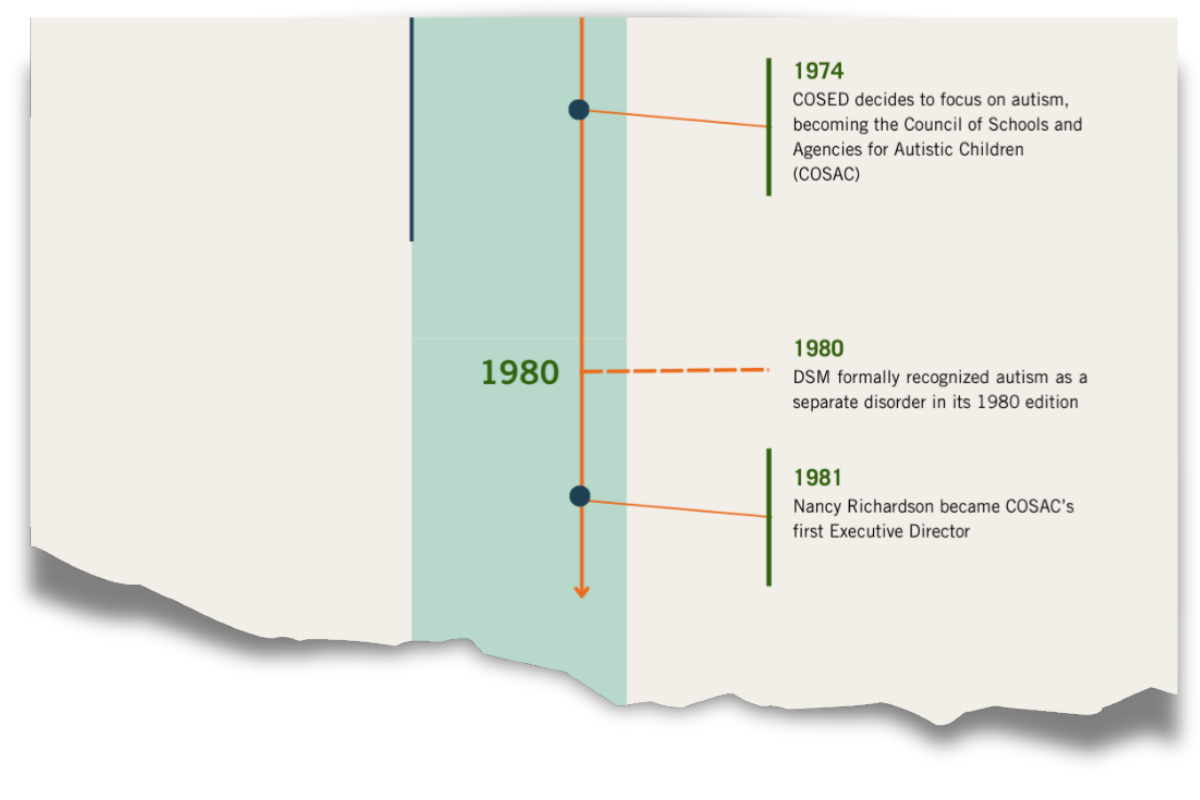

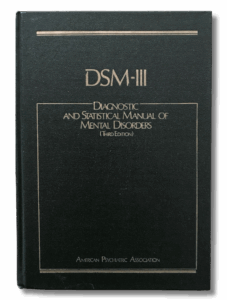

And for good reason — at the time the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), the book doctors use to categorizepatients’ diagnoses, did not include an entry for autism. It only mentioned childhood schizophrenia could manifest with “autistic, atypical, and withdrawn behavior,” leaving children such as Geoffrey in a medical grey-area, often without proper treatment or access to education.

Claire Mahon joined New Jersey’s “Division of Mental Retardation” in 1976. In a 2004 article, she described the awful conditions in the state’s institutions at the time:

“There were as many as 40 people in a ward,” she said. “The staff lined the beds up next to each other. It was not conducive for personal growth, no matter how dedicated the staff had been. The institutions were like Army barracks, no personality. There was not even a night table for personal [belongings] — just a bed in wards segregating men and women.”

The patients were unable to enjoy even the simple pleasures in life, like a fresh strawberry on a hot June day, according to Mahon, because to the institutions, strawberries would be too expensive.

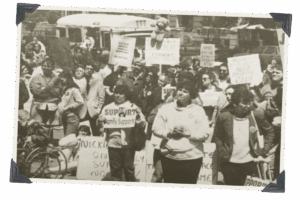

The steady drumbeat of advocates calling for greater community integration and changes to federal Medicaid standards incentivized New Jersey’s institutions to adopt more humane living conditions, reduce the patient to caretaker ratio, and consider who could be served in the community. These changes resulted in approximately 3,000 individuals moving out of the institutions and into community-based group homes or foster care settings. For those first few decades, the federal government fully funded group homes with Medicaid dollars, without requiring states to contribute to them financially.

“The state got a great deal,” Mohan said. “And people who care about developmental disabilities saw this as a commitment from government toward our agenda of community inclusion.”

Meanwhile, Richardson had found an appropriate school and treatment for Geoffrey. And in the course of learning to advocate for her son, she had become an authority on special needs services in the state, helping other families make sense of their own children’s disabilities. In 1981, she was tapped to lead Autism New Jersey, then called the Council of Schools and Agencies for Autistic Children (COSAC) and served on several state advisory boards and task forces.

Richardson and her small team established themselves in that tiny Princeton office and quickly got to work. They created the state’s first group home for autistic women in New Egypt; started parent training programs, grounded in the fundamentals of ABA therapy; and coordinated respite services. Their work helped create the very infrastructure of behavioral health care that the state relies on to this day.

And through the advocacy efforts of groups like Autism New Jersey, more children and adults were integrated into their communities. Individuals with autism who were previously institutionalized were able to live semi-independently in group homes. They went to dances, worked at local businesses — and could pick their own fresh strawberries on a hot day in June.

But from their office in Central Jersey, Nancy Richardson and her team were just getting started.

Autism New Jersey has always operated on the power of connections, and we’d love to hear from you.

From ‘Rain Man’ to Real Change: How Advocates Transformed NJ’s Autism Landscape

From ‘Rain Man’ to Real Change: How Advocates Transformed NJ’s Autism Landscape Breaking Barriers | How autism advocates rewrote New Jersey’s story for a new millennium.

Breaking Barriers | How autism advocates rewrote New Jersey’s story for a new millennium. As we documented Autism New Jersey’s history, we didn’t have to look too far into the past to find sources of hope. The organization, led by Executive Director Suzanne Buchanan, has been at the forefront of progress in autism treatment, safety and services over the past decade.

As we documented Autism New Jersey’s history, we didn’t have to look too far into the past to find sources of hope. The organization, led by Executive Director Suzanne Buchanan, has been at the forefront of progress in autism treatment, safety and services over the past decade.