When a New Jersey mom noticed her twin boys weren’t acting like others their age, she reached out to Autism New Jersey. We’ve walked alongside her for more than 30 years.

When a New Jersey mom noticed her twin boys weren’t acting like others their age, she reached out to Autism New Jersey. We’ve walked alongside her for more than 30 years.

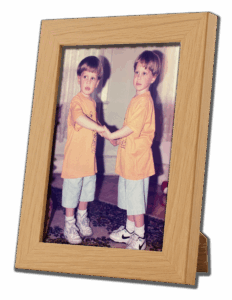

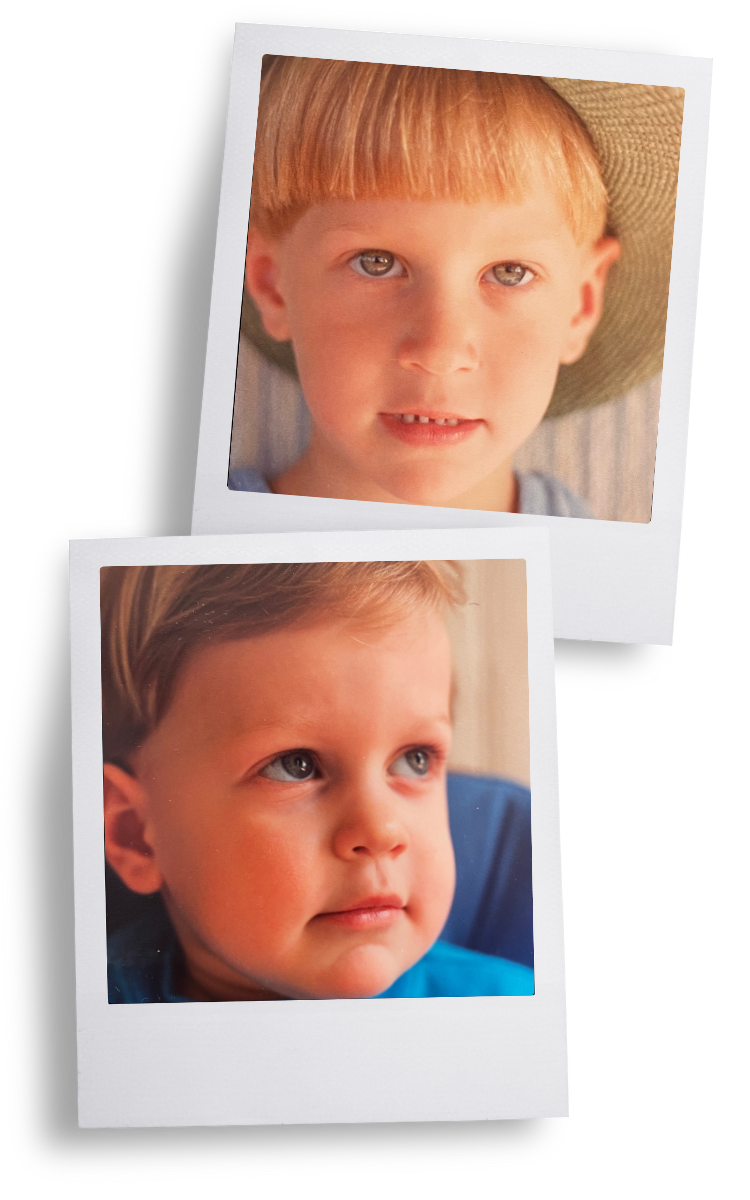

When Mary gave birth to identical twin sons on Christmas Eve in 1988, she felt like she had won the lottery. But less than two years later, she knew her boys were not like others their age.

Robert and James didn’t seem to notice if Mary was upset, nor did they miss her when she wasn’t home. They didn’t interact with each other and behaved as if they were deaf. Their speech was delayed. They flapped their hands, walked on their toes, and made little if any eye contact. They lined up their toys instead of playing with them.

“This was not the family I had planned on,” Mary said.

Mary and her husband Charlie resolved to get their sons the help they needed. Charlie was a freelance artist, while Mary worked for Toys R Us, so it was decided that Charlie would “do the heavy lifting,” Mary said.

After the twins’ diagnosis, one of the first things their doctor advised Mary and Charlie was to call the helpline at Autism New Jersey. (The organization was then known as the Center for Outreach and Services for the Autism Community.) Mary was able to get information about schools, parent training and support groups. At the Autism New Jersey support groups, she found other parents “who were struggling with the same thing.” The moms were very willing to share the doctors and programs and other things they were trying to help their kids, she said.

Mary said she has reached back out to the Autism New Jersey Helpline over the years, for information about doctors and other resources, though “it was really in the early years that I needed the most help.”

The family was able to get the boys into Princeton Child Development Institute (PCDI) when they were 3 years old. They’ve been there ever since.

“I felt like I got them into an Ivy League School,” Mary said.

PCDI not only teaches the kids; they teach the parents how to use ABA at home. The school was featured in a 1990s documentary series called The Nature of Things with David Suzuki, in an episode about autism called “The Child Who Couldn’t Play”. Both Robert and James are in the film.

The twins, now 36, live with their parents in a green multi-level home in Bridgewater, New Jersey, with a pool and big yard where they can play frisbee and badminton. Robert, now called Bob or Bobby, is a talented piano player with perfect pitch. James is a gifted artist like his parents. Their life has been filled with structure, growth, bumps and love.

Autism symptoms in the twins are similar, though behaviors are more profound with Bobby, according to their mom. Both can speak but have no conversational skills. Bob can do complex multiplication problems in his head; both can say their alphabet and spell words backwards and forwards. Mary and Charlie embraced these “superpowers” and encouraged them.

“We had a lot to teach them,” Mary said. “But they had far more to teach us.”

Identical twins develop from a single fertilized egg that splits into two embryos and share the same DNA. Studies have found that when one identical twin has autism, chances are likely that the other twin has it, too, though the severity of symptoms can vary.

James has been creating art with markers since he was 4 years old. Bobby has been playing piano since he was 10 and has performed at local nursing homes.

When Charlie was teaching the boys how to play sports, he could tell they weren’t paying much attention and just wanted the game to end. He began teaching the boys to count during the game, and the boys became more interested. Bobby likes to count to 300 before moving on to the next activity. He’ll often announce “300” to end a game, even if he hasn’t actually reached 300.

While there are certainly superpowers, there are also other behaviors the family has had to deal with. The boys used to freak out from the sounds of vacuum cleaners and running water but were desensitized with the help of PCDI. They still can’t tolerate the sounds of fire alarms, barking dogs and whistles.

Both have obsessive-compulsive tendencies at times. Bob’s compulsions shows up when he gets in and out of the car; James’ rituals are more subtle, Mary said, and can be seen when he lines up his lunch items. When a bug flies by Bob, he starts hitting himself. He also has a habit of smashing birthday cakes – even those that are not his own – when he hears the “Happy Birthday” song.

Bob has had gastrointestinal issues, while James sometimes goes for days without eating when he’s upset about something, Mary said. Bob has a severe issue with intercoms, and in stores, he’ll jump up and try to reach the equipment to turn it off. James likes to cool off in aquariums, while Bob has fixed the glasses of strangers wearing them on the tips of their noses.

Mary, now retired, drives her boys to PCDI every morning, and Charlie picks them up in the afternoon. Both twins work alongside a job coach several days a week: Bobby at Sanofi and James at L’Oreal.

Mary and Charlie are now in their 60s. Until recently, they figured the twins would live at home with them indefinitely. But their way of thinking changed as they got older and realized they wouldn’t be around forever. Mary reached back out to the Autism New Jersey Helpline, which gave her information about guardianship and aging. They have been looking for the right group home for their boys.

“They’re our whole lives,” Mary said. “But it’s getting harder for us.”

Autism New Jersey provides free, lifelong help for families navigating an autism diagnosis. Call 800.4. AUTISM.

Other Relevant Autism New Jersey Resources:

- Autism and Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder connection

- Family Wellness for Caregivers

- Diagnosis page

- Doctor referral database

- Guardianship information

- Housing information

When a New Jersey mom noticed her twin boys weren’t acting like others their age, she reached out to Autism New Jersey. We’ve walked alongside her for more than 30 years.

When a New Jersey mom noticed her twin boys weren’t acting like others their age, she reached out to Autism New Jersey. We’ve walked alongside her for more than 30 years.